Research

The ultimate aim of the modern movement in biology is to explain all biology in terms of physics and chemistry

–Francis Crick

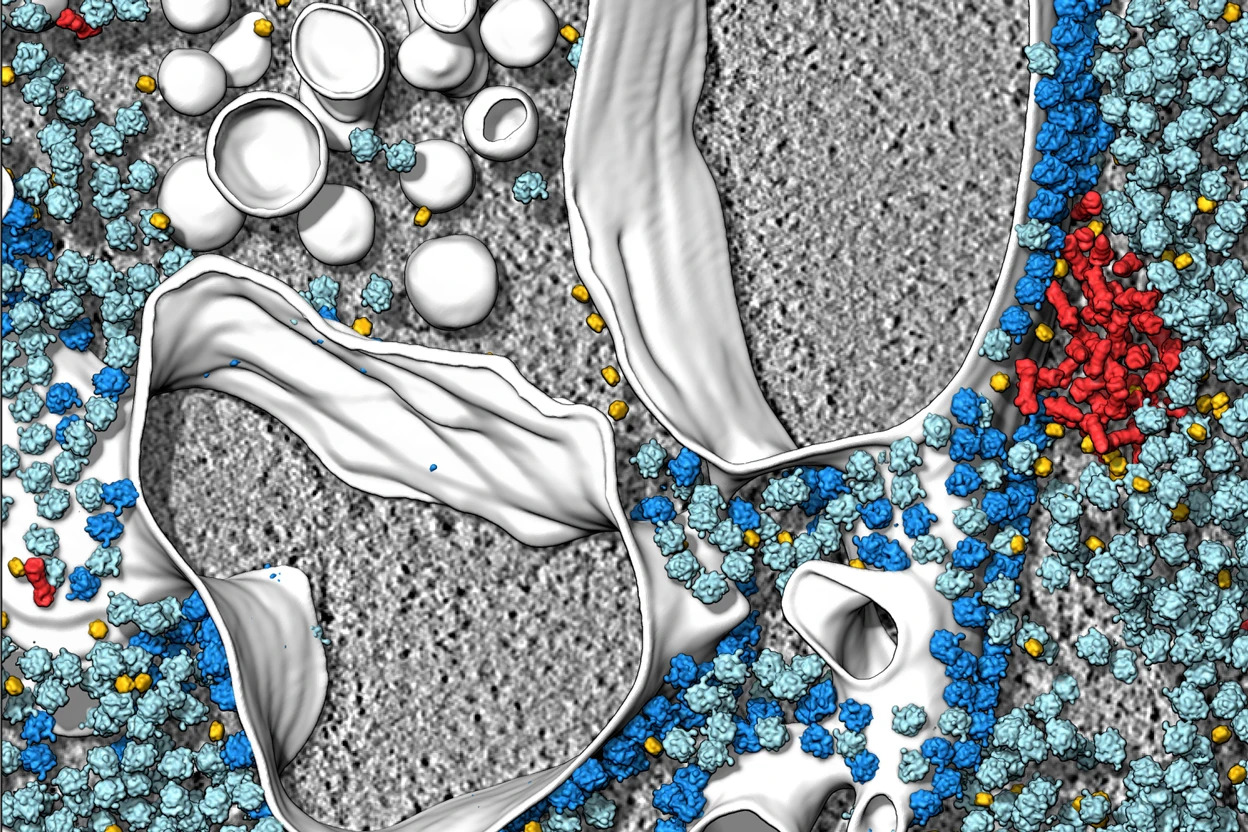

The most striking feature of biological cells is that they are overcrowded with diverse biomacromolecules. For instance, approximately 34-44% of E. coli cytoplasm volume is occupied by macromolecules, which makes it, paraphrasing Skolnick, crowded to a similar extent to Times Square on New Year's Eve (Skolnick, 2016). Such crowding impacts the physical chemistry of the intracellular milieu in a complex way.

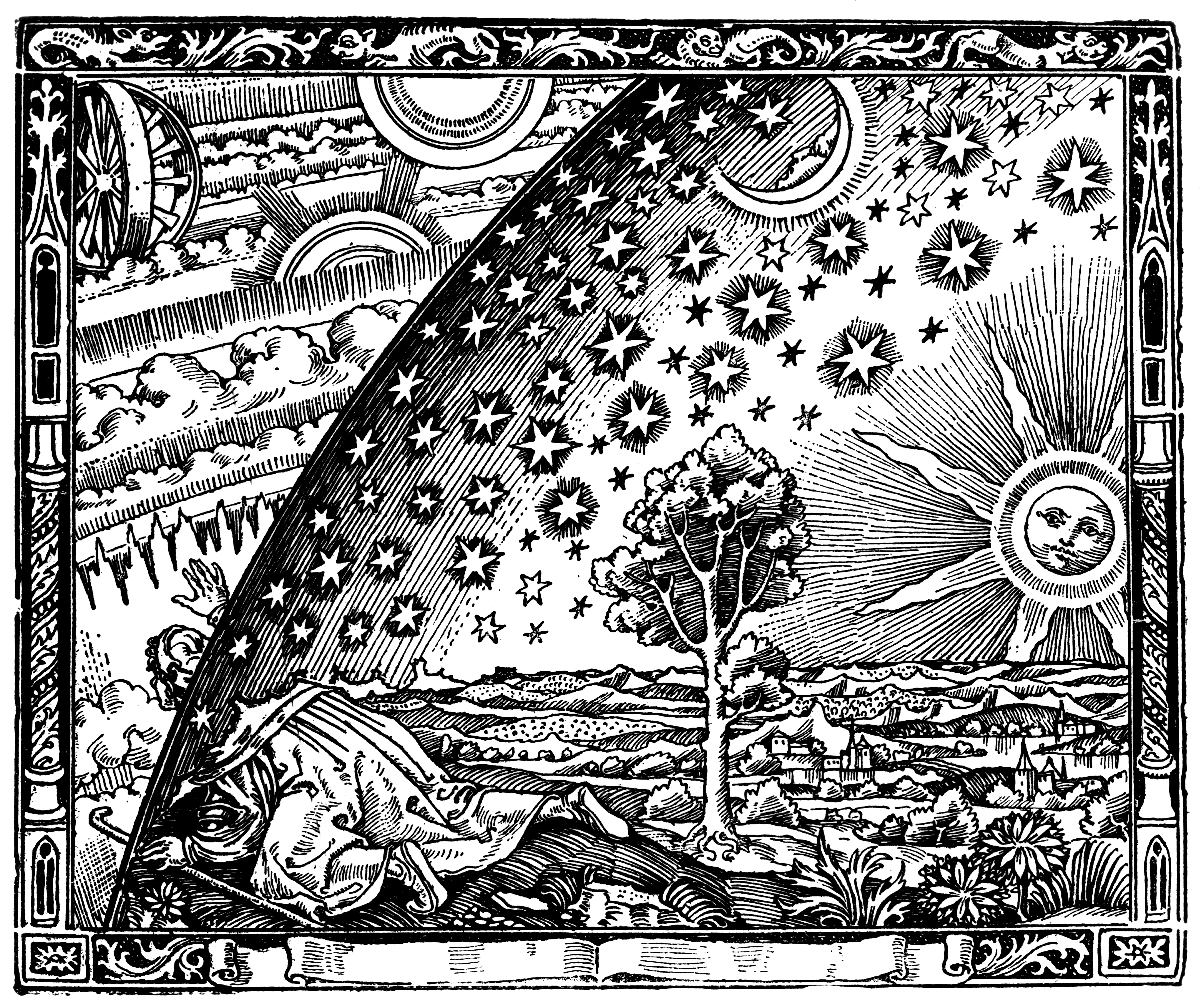

Quickly growing body of high-resolution cell images leads to the emergence of a more precise picture of the biological cells at the nanoscale. In some sense, it is analogous to the accurate and solicitous astronomical observations of XVIth-century Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe, who authored the famous star catalog and noted the precise positions of planets over many years. These experimental results then paved the way for his more broadly recognized successors: Johannes Kepler (assistant of Tycho Brahe) and sir Isaac Newton, who revolutionized science by finding general laws governing celestial mechanics.

Nowadays, one of the grand challenges of the XXIst-century science in general, and computational biophysics in particular, is the development of computer code simulating the biological cell in a quantitative and predictive way, which we could name CELLestial mechanics

. While the stars

of cellular biophysics, i.e., protein structures, are to a large extent cataloged, thanks to ambitious projects such as Protein Data Bank and AlphaFold, the tracks over which the CELLestial

bodies move are still missing.

Cell inner workings stem from the microscopic dynamics of the macromolecules constituting it, such as proteins, ribosomes, and nucleic acids. However, although we are undoubtedly at the dawn of the exascale computing era (Singharoy, 2023), the first-principle simulations of whole cells are currently unattainable and will probably remain so in the coming years. Netz and Eaton estimated that it would take ca. 1 billion years to run such a simulation of one of the tiniest unicellular organisms, M. genitalium (around 3 billion atoms), for the duration of its doubling time, which is ca. 2 hours (Netz, 2021). Assuming that the exponential rise of computational power will continue in line with Moore's law, which is somewhat unrealistic, these simulations would become feasible no earlier than 50 years from now.

Thus my broad research goal is to understand the laws of CELLestial mechanics

on a coarse-grained, mesoscopic level, which is computationally more feasible and conceptually less complex. In contrast to Demis Hassabis, CEO of DeepMind, I want to believe that we are not doomed to machine learning in the pursuit of in silico whole-cell models of the future.

Adapted from my Thesis

References:

- (Netz, 2021) Netz, R. R., & Eaton, W. A. (2021). Estimating computational limits on theoretical descriptions of biological cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 118(6), e2022753118.

- (Singharoy, 2023) Singharoy, A., Pérez, A., & Chipot, C. (2023). Biophysics at the dawn of exascale computers. Biophysical Journal, 122(14), E1-E2.

- (Skolnick, 2016) Skolnick, J. (2016). Perspective: On the importance of hydrodynamic interactions in the subcellular dynamics of macromolecules. The Journal of Chemical Physics, 145(10).